Was Judas Iscariot a vampire?

A reflection on the betrayal of Jesus as the basis of vampire lore

If folklore teaches us anything, it’s that bad decisions can cast very long shadows -- sometimes eternal ones.

When most people picture the “original” vampire, they think of Vlad Țepeș (also known as Vlad the Impaler),15th-century prince of Wallachia, whose cruelty and rumored taste for blood inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula (at least in part).

Yet while Vlad’s brutality was very real, the literary vampire’s roots may lie in an older, more infamous figure: Judas Iscariot. Long before Gothic novels or Transylvanian castles, Christian tradition cast Judas, the apostle who betrayed Jesus, as cursed, restless, and beyond redemption. In some folkloric interpretations, his punishment was to wander the earth eternally, shunned by God, doomed to thirst for the very blood of Christ he had once spurned.

For those who aren’t up to speed on the New Testament, the gist of the story is as follows:

Judas Iscariot was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus, his inner circle of followers.

In the story of the Passion, Judas agrees to betray Jesus to the authorities for thirty pieces of silver (Matthew 26:14–16).

His betrayal comes in the form of a kiss, a prearranged signal to identify Jesus to the soldiers (Matthew 26:48–49).

Judas’s betrayal leads directly to the death of Jesus by crucifixion.

Kiss of Judas. c. 1305

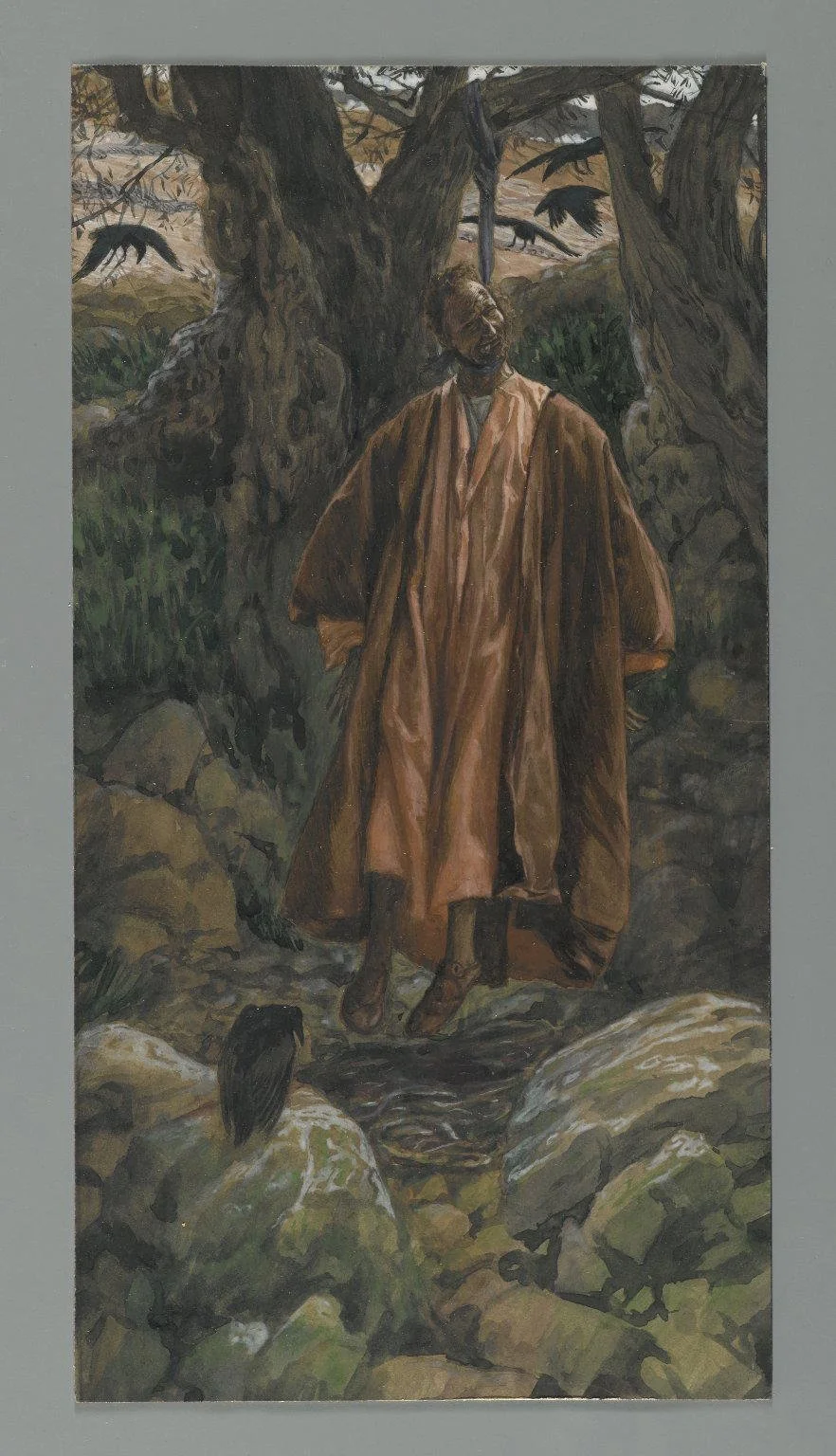

Wracked with guilt afterward, Judas dies tragically, in a manner that the Bible reports in two conflicting but equally dramatic accounts:

Hanging (Matthew 27:3–5) – After trying to return the silver to the priests, Judas hangs himself.

Falling and Bursting Open (Acts 1:18) – He falls headlong in a field, and his body bursts open, spilling his entrails.

James Tissot,Judas Hangs Himself (Judas se pend), 1886–1894. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper, Brooklyn Museum.

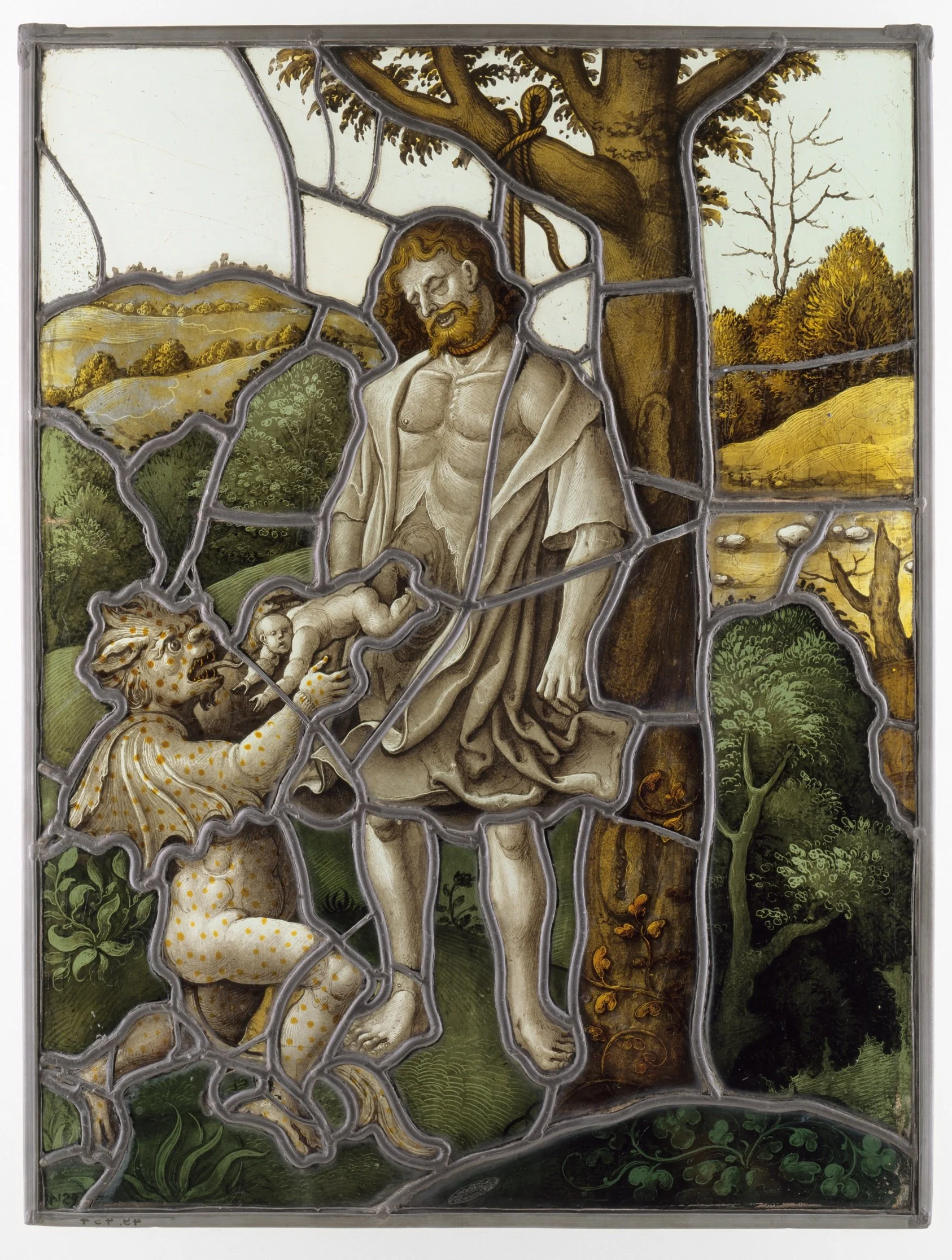

The Hanging of Judas, c. 1520; Unidentified artist; Alsatian or Southern German, from the Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

In this stained glass panel, we see Judas hanging from a tree. A small, bat-winged demon appears to extract (perhaps violently) Judas’s soul, depicted in the startling form of an infant emerging from his ruptured belly.

It is believed that Judas hung himself from an elder tree. A fungus called the “Judas’s ear” mushroom (auricularia aricula judae)— later shortened to “Jew’s ear” grows on elder trees.

Judas Becomes the Archetypal Vampire

Medieval imagination and later Gothic literature ran with the idea of Judas as the prototypical vampire because his death ticks every box for “unease”. In European superstition, suicides and violent deaths were the cause of restless dead, or revenants, a French term for those who return from the grave. Vampires, in their earliest folkloric forms, were often just that: revenants who wandered the night to trouble the living (Barber, 1988).

Vlad Țepeș (aka Vlad the Impaler) Prince of Wallachia

By Anonymous - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=145990532

AI-generated image of Judas Iscariot as a vampire

Let’s imagine Judas’s restless soul doomed for eternity and consider the following aspects of Vampire lore:

Why would a vampire recoil from the sight of a cross?

Because the crucifix is a symbol of the grace he forfeited and a painful reminder of the betrayal of Christ.Why does sunlight destroy a vampire?

Having rejected divine light, he must now live in eternal shadow. A creature who rejected the “light of the world” (John 8:12) is now condemned to shun literal light, perishing in the sun’s rays.The cycle of sunrise and sunset echoes the life, death and resurrection of Christ… i.e. the sun (son) rises after nightfall (death) to bring light to the world. In this sense, Jesus, who has gained everlasting life, triumphs over Judas, whose unnatural death results in endless torment and unrest.

Why is silver fatal to vampires?

Judas sold out Jesus for 30 silver coins, and his blood curse became silver’s searing sting. Silver is linked to the moon, the feminine, darkness, and yin energy. In vampire lore, silver is also the metal that burns the undead, purging corruption on contact. In this sense, it almost feels inevitable that the coins used to extinguish the sun’s light would be silver, not gold.Why no reflection in mirrors?

Folklore says mirrors reflect the soul; Judas, cut off from grace, has none to show. (Like gingers, but more on that later.)Why does the vampire thirst for blood?

In Catholicism, the wine served during communion at Mass becomes the blood of Christ through a process called transubstantiation. Denied this sacrament, Judas thirsts for blood in the only form he can take it: the living. But whereas Christian communion (i.e. drinking the blood of Christ from a sacred chalice) is life-affirming and spiritually purifying, the vampire’s bite is a direct and grotesque inversion of this process, damning the vessel to a state of undeath. Taking this idea to the extreme, the Judas-vampire is literally thirsting for the blood of Christ, which has been denied to him. If this is true, Catholics who have recently taken Communion would be the most attractive targets for vampires as they alone would have consumed the sacred blood.Why does Holy water burn a vampire?

Holy water is believed to be imbued with divine power through the blessing of a priest. From a theological standpoint, holy water isn’t just clean water; it’s a sacramental, meaning it has been set apart for sacred use and symbolizes purification, spiritual protection, and God’s grace. Being in contact with something so closely tied to the sacred is painful or even destructive to the vampire. The reaction works as a kind of supernatural polarity: the consecrated water represents life, purity, and God’s authority, while the vampire represents death, corruption, and separation from God. In the same way the crucifix is a reminder of Christ’s victory over death, holy water is an active agent of that victory, making it anathema to creatures who are caught in a state of spiritual death.

What about garlic?

This one probably came later as a generalization of folklore practices from Southern Europe. Garlic was a folk remedy for plague and evil and would naturally repel a cursed, unclean revenant.***

Count Dracula recoils from a cross in the film, Dracula

Vampire Eric Northman bursts into flames after being exposed to the Sun in the Season 6 finale of True Blood

Stay safe out there: Garlic, Holy Water and Crucifixes, three essential elements of a Vampire-protection kit; House of Good Fortune Collection

In short, Judas carries every mark of the Gothic vampire: a traitor to light, doomed to wander, terrified of the sacred, and hungry for the one thing he can never truly receive.

Before we wrap up, let’s explore one more aspect of vampire lore that is related to Judas Iscariot.

A Digression on Red Hair as the Mark of the Damned

Have you heard the expression that gingers (like vampires) don’t have souls?

This idea became popular in the mid-2000s as an internet meme, largely fueled by a 2005 South Park episode (Ginger Kids), in which the characters teased red-haired, fair-skinned kids. The joke was later amplified by viral YouTube videos, especially the 2006 “Gingers Do Have Souls” rant, which both spread and parodied the stereotype, which plays on older prejudices against red hair.

Although there is no direct support in the Bible for the claim that Judas was a redhead, medieval artists sometimes portrayed Judas with red hair and beard. Over time, the idea of Judas as a ginger took hold and was basically accepted as fact. In 2010, Time magazine published a list of Famous Red Heads and Judas Iscariot was listed first, along with Thomas Jefferson and Lucille Ball.

What is going on here?

The image of Judas as a red-haired traitor was not accidental. In medieval European art and literature, red hair carried layers of symbolic meaning: treachery, moral danger, and, in some contexts, otherness.

In addition to witches, mermaids, vampires, and bad luck in general, red hair signified a very specific type of religious otherness. In particular, red hair became associated with Judaism in Christian Europe, particularly in Southern Europe where red hair was less common. (Note: While red hair is most prevalent among people from Scotland, the Ashkenazi Jewish population of Poland has a similar incidence of red hair.)

So while there is no inherent link between Jewish identity and hair color, medieval Europeans, steeped in superstition and anti-Semitism, often used physical traits as moral shorthand. Red hair stood out, and Christian artists and writers linked it to the “otherness” of Jews, feeding into broader stereotypes of deceit and betrayal like “blood libel,” the idea that Jews need Christian blood to perform secret rituals.

With this context, let’s review the Retable de la Passion du Christ, which currently resides in the Musee Unterlinden in France.

This is perhaps the most famous and most frequently cited painting of Judas depicted with stereotypical Jewish features. It is from the Colmar altarpiece, which is now housed at the UnterLinden Museum. The artist is Caspar Isenmann, a Gothic painter from Alsace.

Detail from the Colmar altarpiece above…Here we see Judas leaning in to kiss Jesus. He is painted with orange-red hair and beard and a prominent hooked nose. Jesus, in contrast, has brown hair, a slightly receding hairline and can barely suppress an eye roll. His expression seems to say, “I am so over this.” (Note: granted, there is a lot going on in this painting, but please don’t overlook dude the hideous visage of the dude on the far right. )

Depicting Judas with red hair, then, was a visual cue that marked him not only as a traitor to Christ, but also as a symbolic Jew, embodying the anti-Jewish sentiments of the era.

This artistic choice reinforced the dangerous narrative that Jewishness equated to treachery, a trope that fueled centuries of persecution. Red hair, in this way, became a double marker:

A warning sign of moral and spiritual corruption.

A reflection of the Christian imagination of the Jewish “other”, folded into the story of the ultimate betrayal.

But, wait…

While The House does not seek to deny — or even minimize — the existence of anti-Semitism in Europe at that time, it is worth noting that a far larger number of works — many of which were much more prominent — did not portray Judas with red hair.

For example, in The Last Supper by Rubens (above), Judas is depicted with dark hair (and a guilty expression). Similarly, in Giotto’s Kiss of Judas (also above) he is beardless and his hair is dark. And in perhaps the most widely known depiction of The Last Supper by Leonardo DaVinci, Judas is once again painted as a dark-haired person.

In this restored version of DaVinci’s The Last Supper, we see Judas seated fifth from the left, clutching a bag of coins and looking directly at Jesus. Among several apostles with red strawberry blonde hair, his dark hair and beard stand out.

Here, Jacopo Bassano has painted the scene with a dark-haired Judas seated in the foreground next to a cat, a symbol of disloyalty and treachery.

In this clip from History of the World, Mel Brooks, playing a waiter at the Last Supper, asks Judas if he wants a beverage. Judas is shown in light green with dark hair and beard. Although this film might seem schtick-y to modern audiences, it is a classic that is well worth watching.

Jesus Was a Ginger Too??

To complicate matters, many works depicted Jesus Christ himself with flaming red locks — along with Mary, his mother, and various red-haired apostles.

But to state the obvious: Jesus, like Judas, was Jewish, as was his mother and all of the other apostles. So is this more anti-Semitism? Or something else?

Pieta by Italian artist Agnolo di Cosimo a.k.a. Il Bronzino. Here we see Jesus and his mother, Mary, depicted will bright red hair.

Judas Thaddeus aka “Saint Jude,” Patron Saint of Lost Causes, depicted with bright red hair and beard. He is often confused with Judas Iscariot, but they are two different people. (Though some say that Judas was not an actual person but a narrative construct…")

The First Vampire? A Final Word…

By the time Gothic vampire lore emerged, the red-haired Judas carried not just the weight of personal guilt but the shadow of Europe’s anti-Semitic iconography—a figure visually coded as cursed, dangerous, and estranged from the Christian world. Judas is the one hunched, shadowed, or visually separate, his appearance already hinting at his eternal estrangement.

While no medieval priest ever preached that Judas stalked the night as a vampire, folklorists and occult enthusiasts have noted how naturally his story fits the revenant pattern. His kiss of betrayal was cast as the first vampire’s bite, a parody of intimacy, and his endless thirst as the dark mirror of sacramental Communion.

But the tale of Judas the Vampire is not doctrine; it’s a folk mirror, reflecting how fear and faith entangle in the human imagination. It reminds us that even the holiest stories cast shadows—and that betrayal, like folklore, has a way of refusing to stay buried.

Whether we picture him dangling from a tree, his soul pried loose by demons, or wandering eternally under the weight of silver, Judas Iscariot sits uneasily between scripture and superstition. He embodies every feature of the vampire archetype: cursed by silver, shunning the light, recoiling from holy things, hungering for blood. Even his red hair—sometimes painted bright as flame, sometimes not—served as a medieval shorthand for treachery and otherness.

Was Judas truly the first vampire? Of course not. But in the Gothic imagination, he was too perfect a candidate to resist: a restless revenant condemned by betrayal, forever cut off from grace, and thirsting for the one thing he could never again receive. In the end, Judas may not have risen from the grave, but his shadow lingers in the myths we tell of those who do.

Further Reading:

Montague Summers (The Vampire: His Kith and Kin, 1928)

Paul Barber (Vampires, Burial, and Death, 1988)

Massimo Introvigne, The Blood Libel Anti-Semitic Myth, Bitter Winter, A magazine on religious liberty and human rights, 19 March 2022

Was Jesus Ginger?, a more thorough review of artwork (and Biblical text) where Jesus is depicted with red hair