“I think I’ve been poisoned by my constituents!”*

Today we are going to explore two animal curios that were used as amulets against poisoning: the toadstone and the narwhal’s horn.

***Why is this a thing?***

Apparently, being poisoned was a subject of preoccupation in the Middle and Renaissance ages. It seems that scoundrels were going around poisoning people for various reasons — vengeance, political gain, etc. Maybe poison was the only viable option for a woman to get out of a bad marriage? Or perhaps people were simply afraid of accidentally ingesting poison?

Whatever the reasosn, people were not content to just eat and drink substances willy-nilly with no recourse; they had to do something to protect themselves. And what do people do to protect themselves? They make and use amulets.

Amulet #1: The Toadstone

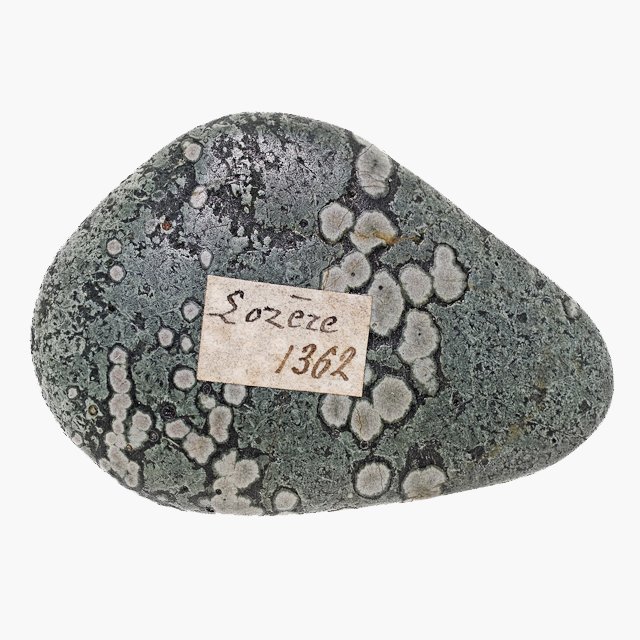

A toadstone is a round, brown, lusterless “gemstone” that resembles a Milk Dud. Toadstones were also known as, uh, “crapaudine” (seriously) and these “jewels” were thought to originate in the heads of toads.

Notably, William Shakespeare included a reference to this erroneous belief in As You Like It: “Sweet are the uses of adversity; Which, like the toad, ugly and venomous, Wears yet a precious jewel in his head.”

The advice from one magical treatise was to take the stone from the toad’s head during a waning moon, and voila!… you will have a powerful amulet. (The method of extraction involved placing the toad in an earthenware vessel until it basically starved to death and all that was left was its skin and bones.)

But it’s difficult to see how this advice would work in practice because in reality the so-called “toadstone” is actually the fossilized tooth of a now-extinct fish known as “Lepidotes.” Lepidotes had a palate of hard, domed “teeth” that it used to crush the shells of mollusks.

Chocolate-covered caramel candies called “Milk Duds”

Toadstone ring, c. 1500-1700, from the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum

Teeth of Lepidotes maximus, Natural history museum of Neuchâtel. Imagine finding this object along a riverbed. —What would you think it was?

Although they are not much to look at (in The House’s humble opinion), there is something intriguing about the natural shape and smoothness of the toadstone, which also made them easy to set in the bezel of a ring or pendant without much modification. (If you’re interested, The British Museum has an outstanding collection of toadstone rings and amulets for your perusal.)

Because they are so distinctive-looking people ascribed mystical and supernatural powers to toadstones. For example, toadstones were thought to protect against diseases of the kidneys and bowels, and those who suffered from gastrointestinal ailments were encouraged to swallow a toadstone to clean the digestive tract — like a modern-day juice cleanse!

The practice of using stones to treat illness or injury is called lithotherapy.

Toadstones were also used to treat insect and snake bites, because it was believed that the stone could draw venom out of a wound. And here’s where it really gets interesting…

There was a parallel folk medical practice involving a “snakestone” (sometimes called “blackstone”), which was thought to come from the head of a cobra. Snakestones were called “piedras della cobra de Capelos” and came to Europe primarily from India in the middle of the 17th century.

A slightly different take on snakestones from the collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum: “Variolites are green and white crystalline rocks, and are commonly found in the region of the Durance river in southeastern France. The mottled markings resemble those on the skin of a snake, and may be why they became known as a ‘snake stones’, ‘venom stones’, or ‘poison stones’.”

In practice, one would apply the stone to the wound, where it would draw out the poison. According to certain accounts, the stone would stick to the wound like a suction cup. When the venom had been absorbed, the stone would drop off and be placed into a bowl of milk (preferably human; seriously) to remove the poison and cleanse the stone for further use.

Medical practitioners of this era actually conducted experiments on snakestones by using them to cure animals (and humans) who had been bitten by snakes. Spoiler alert: sometimes the cure “worked;” sometimes it didn’t, which is probably more attributable to the fact that only some snakes are venomous than to the power of the stones. What’s even more incredible is that the efficacy of these stones as anti-venom was still being tested in the 21st century!

So…we can see, then, that it wasn’t a far leap from snakestone to toadstone in terms of venom-drawing capabilities. Toads, like some snakes, were thought to be venomous so it stands to reason that a “stone” from either creature would serve as an antidote to poisoning. But the toadstone was also believed to emit heat or change color in the presence of poison, thus alerting the wearer to danger or possibly death. Obviously, this would have been a huge advantage in a culture preoccupied with protecting against the dangers of being poisoned.

Fossil of Lepidotes, Smithsonian

Amulet #2: The Narwhal’s Horn

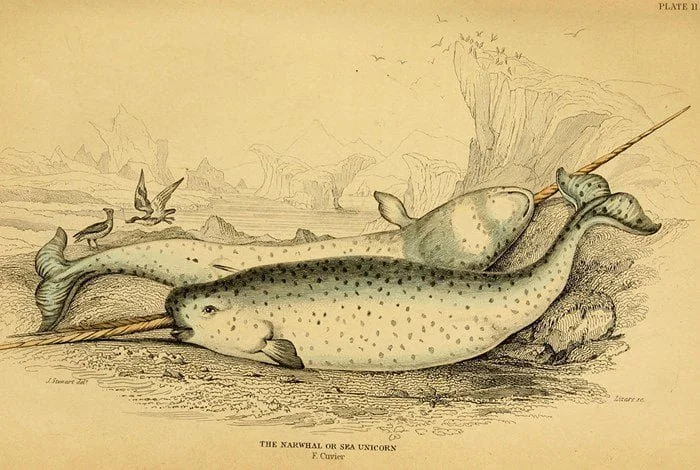

The belief that a narwhal’s horn could cure poisoning stems from the misidentification of a narwhal’s horn as a unicorn’s horn, which is completely understandable when you compare the two.

Unicorns have been a part of mythology and folklore for thousands of years. The ancient Greeks and Romans believed that unicorns were real animals, and wrote about them in natural history texts. In the Middle Ages, Europeans saw unicorns as symbols of purity and grace and believed that their horns had healing powers. Some, including Queen Elizabeth I, believed that drinking from a cup carved from a unicorn horn would prevent poisoning. So naturally, a unicorn’s horn would be regarded as a precious and incredibly valuable object. The problem, however, is that it is impossible to drink from a unicorn horn because unicorns are mythical creatures that do not exist in this world.

Enter the Narwhal…

The narwhal is a medium-sized whale with a long, pointy tusk protruding from the front of its head. The tusk is actually a tooth. Narwhals inhabit the icy waters of the Arctic, where they cruise around preying on halibut, shrimp and squid and being preyed upon by Inuit hunters. Because narwhals live in a relatively isolated part of the world, they are difficult to study and human interaction with them was limited. But encounters with these improbable-looking creatures occasionally occurred and even inspired Inuit myths about how the narwhal got its horn.

So let’s step back in time. Imagine it’s the early 16th century and you are strolling along the beach when you stumble upon a long, pointy, twisting horn. Or maybe an adventurous, sea-faring trader offers the horn to you. If you’re from Europe, it’s highly likely that narwhals are unknown to you, so you conclude that the horn must be from a unicorn. What else could it be?

The Narwhal (or “sea unicorn”), from the collection of the Smithsonian Institute.

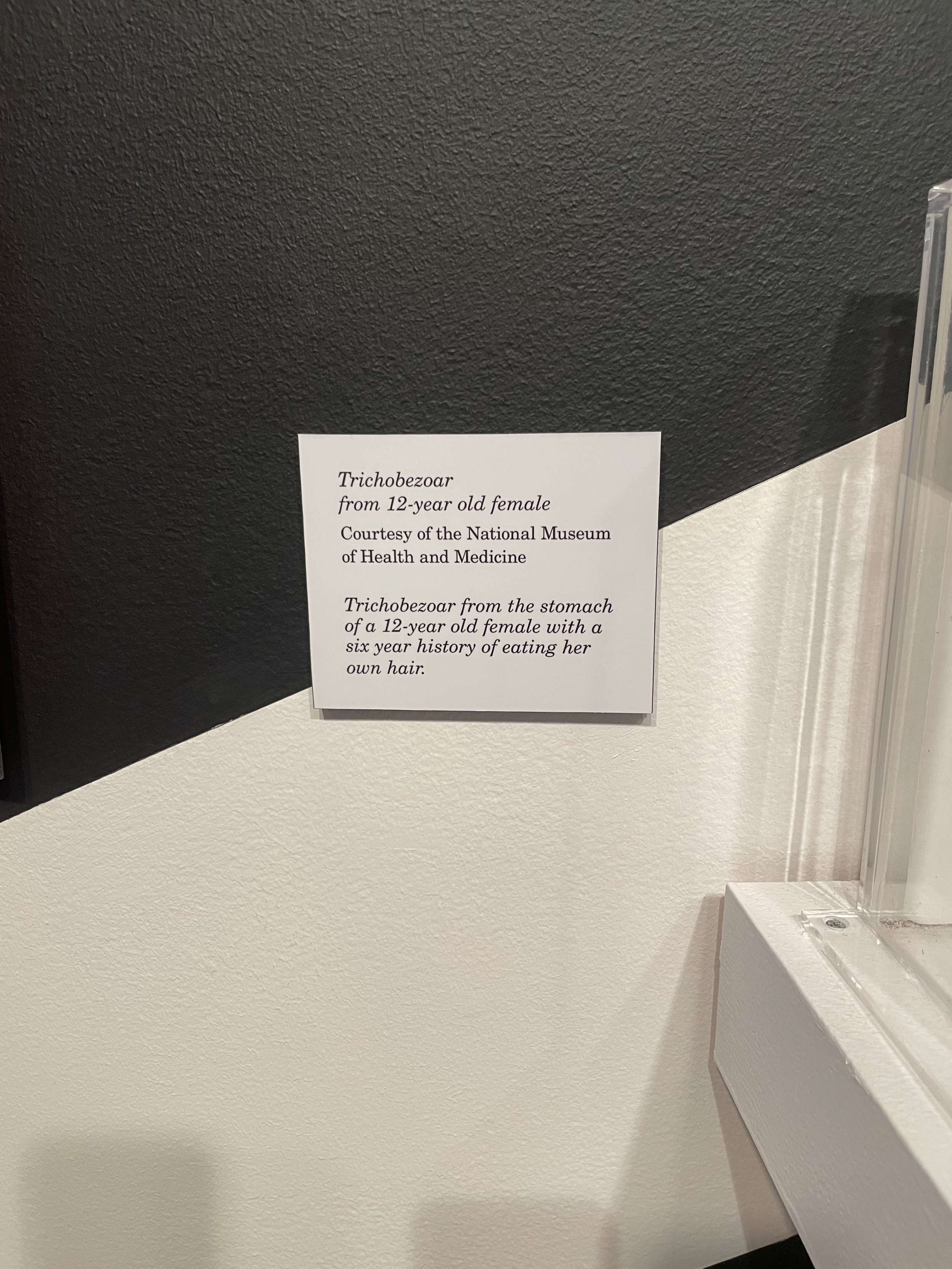

Goa Stones and Bezoars

As a substitute for unicorn horn, the narwhal’s horn was regarded as a precious substance and as such, it was a common ingredient in a type of medicinal cure-all known as a “Goa Stone.” Goa stones were manufactured versions of the naturally occurring masses, called “bezoars,” that occasionally form in the digestive tracts of ruminants like cows and goats. The word “bezoar” was derived from Arabic and Persian words meaning “antidote” and these concretions, which typically consist of calcium phosphate, are highly absorbent. (Bezoars can also form in the human digestive tract, where they are typically composed of hair or other indigestible matter and can require medical intervention.)

Although bezoars were believed to serve as an antidote to poisoning, the problem with natural bezoars is that they are relatively scarce and hard to procure. So a group of Portuguese Jesuits who were living in India came up with a solution — we’ll make our own bezoars!

And there you have the Goa Stone. Sometimes they used a naturally occurring bezoar and added clay, silt, resin and other materials to “stretch” it. As demand for these restorative balls grew, they got creative and added all manner of luxurious and mystical ingredients like pulverized gemstones and “unicorn” (i.e. narwhal) horn. Once assembled, the ingredients were carefully shaped into a smooth sphere and stored in ornately decorated gilded cases, which were said to enhance their magical properties.

In order to reap the benefits of the stone’s curative properties, the user would scrape off a bit of the stone, mix it with water or tea, and drink the concoction.

Pendant, 'The Danny Jewel', in the shape of a ship, with a semi-circular section of a narwhal's tusk mounted in enameled gold suspended by three chains from a ring, c. 1550, from the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Left hand side, pale green oval bezoar stone from a camel, possibly Algerian, 1601-1800. Right hand side, spherical speckled bezoar stone from unknown animal, 1551-1750; Bezoar stones are found in the stomachs and intestines of animals and humans. They are made from things that cannot be digested in the body, such as hair, and fibres from fruit and vegetables. This forms a hard, solid stone. The stones were placed in drinks to counteract poisons from would-be assassins. (It was believed that bezoar stones could counteract any poison.) Image and original data from Science Museum Group

Gold filigree case containing a bezoar, (Goa Stone?) Image and original data from Science Museum Group

And here is a trichobezoar from the stomach of a 12-year female with a six-year history of eating her own hair. It was exhibited at the American Visionary Art Museum in 2022.

So there you have it. To recap:

Here we have two animal curios — a fossilized fish tooth and the tooth of an Arctic whale — both of which acquired magical properties through misperception about what they actually were. In the case of the toadstone, a tooth was thought to be a jewel from a toad’s head; and in the case of the narwhal’s horn, a highly unusual tooth was thought to be the horn of a mythical white horse.

Once the misidentifications had been made, they were incorporated into the folk medical practices of the day.

Questions to Ponder:

Is it significant that both of these curios are teeth that were perceived to be something else — i.e. a jewel and a horn?

Is it significant that both of these curios belonged to aquatic creatures?

What other magical properties were teeth believed to have? And what is it about teeth that sparks association with magic?

Is it a coincidence that both toadstones and bezoars are round, brown masses that were believed to possess magical properties?

The House would be delighted to hear your thoughts on this subject, but for now let’s conclude with this Fun Fact:

In 2019, a man fought off a would-be terrorist on London Bridge by using a narwhal’s tusk as a weapon. It was a truly extraordinary incident.

A magical object, indeed.

* The title of this post is a line from a scene in It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. It will not make any sense unless you watch the show, so The House will not attempt to explain it. IYKYK.

***

Related Reading:

Toadstones, National Museums Scotland.

The Snakestone Experiments: An Early Modern Medical Debate, Martha Baldwin, Isis, Vol. 86, No. 3 (Sep., 1995), pp. 394-418.

Meet the Narwhal, the Long-Toothed Whale that Inspired a Magical Medieval Legend, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 3, 2021.

The Story of the Unicorn, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Man-Made Gut Stones Once Used to Thwart Assassination Attempts, Atlas Obscura

The Madstone, by Thomas R. Forbes, Yale University School of Medicine, compiled in American Folk Medicine: A Symposium, edited by Wayland D. Hand, 1976.

Jin Chan, Money Toad, Bonheur Blog, House of Good Fortune