Naturally Occurring Eye Amulets

Exploring Stones and Shells That Resemble Eyes

In the annals of human history, the use of eye amulets stands as a testament to our enduring quest for protection and well-being. These amulets, revered across cultures and epochs, serve as guardians against the malevolent gaze known as the evil eye. For those who are unfamiliar with the evil eye, it is a malevolent gaze, typically resulting from feelings of envy toward the lookee. Children and livestock are most susceptible to its effects, and the common view is that people with blue eyes are most adept at casting it.

Today all manner of “evil eye” jewelry and related tchotchkes are manufactured and widely distributed, but in ancient times, our ancestors turned to the natural world for their talismans. They believed that certain stones and shells, with their unique patterns and shapes, possessed inherent protective powers. For instance, horn-shaped pieces of red coral, known as cornicelli, were cherished for their ability to ward off evil. Other unusual-looking shells, stones, and other natural objects were also believed to protect against certain ailments and conditions.

In 19th century Europe, the practice of wearing amulets was widespread, despite opposition from institutions like the Catholic Church. People believed that these amulets could shield them from various ailments and the dreaded evil eye. Stones with intricate natural designs, such as fossilized coral, were particularly valued. It was thought that the complex patterns would distract a witch, thereby protecting the wearer from harm.

Heart-shaped amulet of fossilised coral (Krätzenstein) in a silver mount, Bavaria (South Germany), about 1800. From the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Stones with pronounced natural designs, like this piece of fossilised coral, were mainly worn to avoid bewitchment; the witch would be distracted by the complex pattern and so the wearer would escape unharmed. This stone was also said to protect against fevers.

Eye Agates

Apologies for the digression. Let’s now get into the topic at hand — eye amulets. Faithful readers of The Bonheur Blog know that eye amulets are one of the oldest forms of protection against the evil eye. Observe, for example, the Eye of Horus (or wedjat) which was one of the most popular amulets in Ancient Egypt.

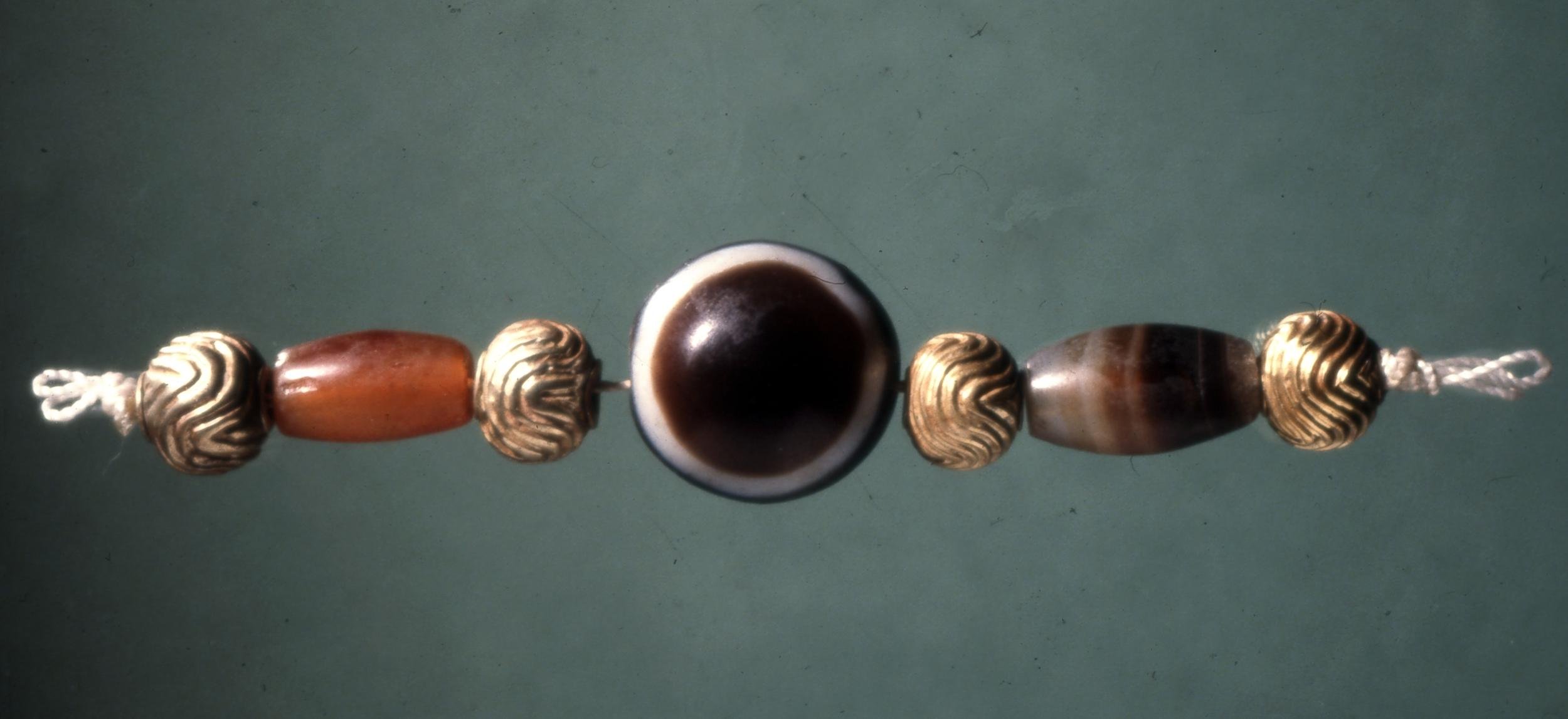

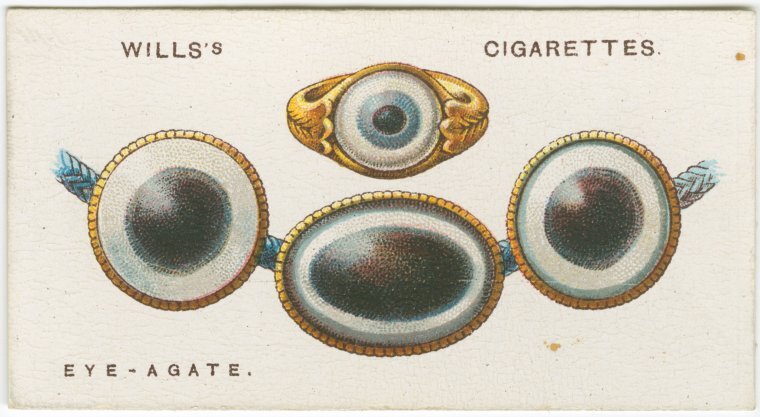

But whereas wedjat amulets were manufactured — typically carved from stone or made of faience or glass — other eye amulets were simply found. The first example we will explore is a certain kind of agate that, when polished and cut, resembles the iris and pupil of the eye. These stones were prized as amulets and incorporated in early jewelry as featured stones or beads with an uncanny appearance.

Operculum Jewelry

The second naturally-occurring eye amulet we will explore comes from Turbo petholatus, also known as the "cat's eye" or "Shiva's eye" snail. The amulet is a part of the snail called the operculum, which means “lid” or “cover” in Latin.

The operculum is a hard, disc-shaped shell that is attached to the snail's foot and is used to close the snail's shell when it is retracted (hence the name). It is about the size of a U.S. quarter and has a spiral pattern on one side. The other side coincidentally resembles a human eye and looks like this:

Given that some of the earliest known jewelry — dating back to the Stone Age — was made using shells, animal teeth and seeds, it should not be surprising that opercula have been used to make pendants, earrings, and other pieces of jewelry for a long time.

Credit: Shell pendant painted with an eye, Paris, France, 1850-1920. Science Museum, London.

Today, the tradition of eye amulets continues, albeit in a more modern context. Jewelry and trinkets featuring the nazar, a symbol of the evil eye, are ubiquitous. Search for “evil eye” on the Chinese retailer Shein’s website and your results will include hundreds of items. These contemporary amulets serve as a reminder of our ancient practices and the timeless human desire for protection and good fortune.